THE MUSTARD SEED.

What began at that scrawny Cuban Committee for Human Rights, that many

classified as quixotic, is at present a notable force due to their

courage, their determination and their moral authority. It is not a

massive movement, but it is the largest of those who have been in any of

the countries which were subjected to communist totalitarianism

throughout the world.

Also, it is very diverse, it includes in its ranks Cubans of all social

strata of the country, medical doctors like Dr. Oscar Elias Biscet,

engineers such as Oswaldo Paya, lawyers like Rene Gomez Manzano,

economists such as Marta Beatriz Roque, poets like Regis Iglesias,

educators such as Roberto de Miranda, philosophers like Jaime Legonier ,

ex-military such as Vladimiro Roca, peasants like Antonio Alonso, trade

unionists such as Carmelo Diaz , housewives like Berta Antunez, and

simple country people such as the brothers Sigler Amaya and many more.

Among them are whites, blacks and mulattoes, Catholics, Protestants and

Santeros, liberals, conservatives, christian democrats, socialists and

all other non-Communist political denominations. And they are from the

extreme western end of the island, as the Pro-Human Rights Party, in

Guane, to the extreme eastern end, as the Youth Movement for Democracy

in Baracoa.

In its shadow and with its momentum has been reborn in notable measure

the civil society of the nation: journalists, librarians, cooperatives,

professional associations, farmers, workers, artists, intellectuals and

independent disabled, among others.

They have achieved international recognition at very high levels, as

witnessed by major prizes for the promotion of human rights granted to

different activists by the European Union, non governmental

organizations and other institutions in different countries. What is

more important, every day they earn more respect among their fellow

citizens.

It should be noted, also, that in Cuba, as elsewhere, important semantic

differences that had importance in the past have been erased. Today, in

the Cuban context, opposition and dissident are synonymous, because

under the classification of "dissidents", "dissent" or "the human rights

people," as the general population calls them, it includes persons

such as Oswaldo Payá , for example, who never belonged to the ranks of

the regime, and others who believed for more or less time in the mirage

of the revolution.

We can say, therefore, that the current internal dissident movement is a

vivid display of the entire Cuban nation and that it is, today, the

most important agent of change within the island. In it is fulfilled the

parable of the mustard seed, thus from a tiny seed has emerged a

corpulent tree. It would not be prudent to exaggerate their importance

in terms of the correlation of forces with the dictatorship, but neither

would it be to ignore its potential as channeling the desire for

justice, now widespread at the popular level, that originated when those

desires were expressed by only a few.

The dissident movement does not have an effective articulation

throughout the Cuban territory, but I don't think it is an exaggeration

to say that it demonstrates already the ability, when the moment arrives

and with adequate support, power, together with other independent

bodies, religious and fraternal, that offer answers to peremptory

uncertainties, the instability and initial disorder that inevitably

accompany any significant change in a previously totalitarian society.

In summary, since the issue has arisen: if they ask me what the real

importance of the current internal dissident movement, I would say it is

the Cubans having revealed to themselves the possibility of banishing

violence from political struggles and the effectiveness of non-violent

methods in the pursuit of justice.

Cuba inherited old concepts which indicated that the only honorable way

to resolve grievances and disputes was through blood, however evident it

is today that to win by force means that it is the stronger or the

better armed then the other, but not that one necessarily is in

possession of reason or rights. The armed or physical confrontation

became erroneously, the only acceptable proof of courage and honor.

That mentality which ferociously pushed Spaniards and their Cuban sons

to confront each other when the latter justly demanded their

independence, continued to mark the Republic, and that is how we saw

patriots who won indisputable merits out in the fields confronted each

other afterward with the same violence because of political disparities

or ambitions of power, providing our nation’s history with very sad

pages like the death of Quintín Banderas in the times of Estrada

Palma, the racial and veterans confrontations during the government of

José Miguel Gómez and the excesses of the government and the

opposition during the Machado eras.

It is not wanting to judge by modern parameters, and in the light of

experiences they had, to people acting according to the culture of their

time and by what they had learned as good and honorable, and who, on

the other hand, well are indebted for much good that they did. This is

an attempt to dispassionately understand this harmful and

counterproductive tradition of violence that caused rivalries and

grievances passed from generation to generation, without the possibility

of solution. There was always a debt to settle, and it was paid off

with blood, the blood of brothers.

Along with this, we must clarify that none of this implies that one can

condemn a people at one time if he is forced to resort to violence in an

extreme situation, as sometimes one resorts to an amputation to avoid

death, especially where the obstinacy of the oppressors shuts out all

other attempted solution. Countries, like persons, have the right to

defend themselves against aggression. This resort to non-desired

violence, has, nevertheless to be imposed temporarily by circumstances,

and not be a favored option, much less a practice or method of

justifiable struggle.

The syndrome of violence that marked our Republic and to which I

referred to earlier, has had its most cruel expression in the present

regime. We can never forget the executed by firing squads, the tortured,

the fallen in combat, those murdered while trying to escape the island.

We can not nor should we forget the experience of living in fear, the

heroic Calvary of political imprisonment, nor the horror of the acts of

repudiation. It is precisely out of respect and gratitude to the fallen

and what we have all suffered that we have to fight for their

grandchildren and the grandchildren of all Cubans of the present, can

live a different Cuba to the one we had to live in both them and us. A

Cuba where the problems are resolved "among Cubans" in harmony and

civility, not by some imposing it on others. A Cuba, finally, "where the

first law of the Republic is the respect of each Cuban for the full

dignity of man."

The conduct and methods that sunk Cuba and keep it under to the present,

are not the ones that are going to save it. To assume the thankless

task of trying to break the burdensome legacy of violence is the

greatest merit of the dissident movement, because, if achieved it would

be an inestimable good for Cuba, not only for today and for us, but also

for the future, for those who are still to come.

More concretely, I would say that the greatest importance of the

internal dissident movement in Cuba today, is that it has proven that

political action can be consistent with what conscience knows and that

is that the force of reason is, and should be more powerful than the

reason of force.

***

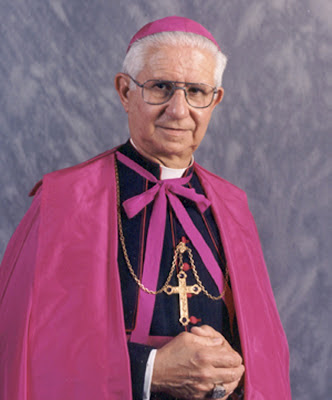

"If what we do for Cuba, we do not do for love, better not do it." - Bishop Agustín Román

CONCLUSIONS.

Everyone knows that there are none so blind as those who will not see. I

believe that only those may try to deny the importance of the current

dissidents in Cuba, but, if one needs a convincing testimony about it, I

think none better than the dictatorship itself: if those opponents did

not represent a real challenge to the regime, then why do they repress

them with such virulence? ... Why jail them? ... Why try to discredit

them constantly?

The skeptics should be reminded that although the end result sought by

the Cuban people has not yet been obtained by dissidents or anyone else,

they have shown that non-violent civic resistance can jeopardize

totalitarianism, as it happened with "

Concilio Cubano" in 1996, in 2001 with the

Varela Project and in 2003 with the ferment opposition that caused the "

Black Spring" of that year, all of which shows that in these methods the potential to trigger the definitive change.

And at this point, it is clear that it would be logical that all Cubans,

both on the island as in exile, ask ourselves what can we do to help

the dissidents? ... We the exiles should ask ourselves what to do,

between them and us, imparting all the possible effectiveness of the

legitimate struggle for the liberation of the common homeland.

I could not offer policy prescriptions nor strategies for action,

because I am not a politician or a strategist. I am a Cuban priest, a

simple shepherd of souls, and as such, could only refer to what I

learned in the light of the Gospel, remember what some of our great

thinkers have suggested and recommend that we not forget the proven

wisdom of our peasants, that which today is called common sense.

I said at the beginning of the urgency to reflect on these issues as we

did today, because of the special circumstances that the Cuban nation is

living at this moment. That same sense of urgency we should have with

regards to the steps we must take. It is not for me to say what are

those steps, but, whatever they will be will move us forward, and not

backwards only if we take them through paths of virtue. ¨No homeland

without virtue," said to us the first who taught us to think and it

occurs to me that I could suggest some of the virtues necessary for our

steps to lead us to the goals of the common good, that we want for Cuba:

1 - Firmness of principle and clarity of the objectives. We must be

aware of what we want for Cuba: true sovereignty, rule of law and

respect for human rights. This sums up all the other just demands such

as, for example, the release of political prisoners, democracy, free

elections, just proceedings, and so on. We should put forward, in

addition, our non-acceptance of formulas that attempt to impede or

obstruct the right of Cubans to freely choose their destination or

promote continuity of this system or something similar, under the

appearance of democracy, openness and reforms.

2 - Equilibrium. Humans are very susceptible to the passion that makes

them lose clarity in their vision of things. Cubans are no exception to

this rule, on the contrary, therefore, we must remember the wise words

of the well named prophet of exile, our unforgettable

Bishop Eduardo Boza Masvidal.

He told us about this, I quote: "The equilibrium is not to dance the

tightrope, but it is to adopt a clear and defined attitude that asks

nothing borrowed from anyone, but is born of good doctrinal training and

a dispassionate and objective study of reality "End of quote.

3 - Unity. Unity in diversity, which is as it should be, but firm unity,

because if we have always needed it, it is essential to us today. You

do not have to explain it to any Cuban how much damage disunity has done

us. It is time to separate the wheat from the chaff. Do not forget what

the Lord Jesus himself tells us in

chapter 12 of St. Matthew: "Every kingdom divided against itself will become desolate. And every city or house divided against itself will not stand."

4 - Prudence and energy. The Servant of God and architect of Cubanness,

Father Varela, recommended to the Cubans of his time in his "Moral and

Social Maxims" not to mistake weakness with caution, noting that it

"tells the man what he should choose, practice and omit in every

circumstance." I would emphasize this valerian maxim, remembering that

the first that prudence indicates is to think before acting. Varela also

noted in "El Habanero", something which seems written for our day. I

quote: "It is not time to entertain ourselves with particular

accusations, or useless regrets. It is only to operate with energy to be

free." End of quote.

5 - Justice, truth, forgiveness and reconciliation. I said earlier that

the cause of the internal dissident movement, the cause of all of us in

the end, is the continued pursuit of justice for the Cuban people. Cuba

cries out to heaven for justice, justice is essential. The truth is the

complement of justice and should be the first condition of our work and

firm foundation of the society. Every Cuban will recognize the truth of

their responsibilities and errors if we want to enter the new Cuba with

the cleanness that we want. At the same time, the country equally

needs of forgiveness and reconciliation in order to have possibilities

of a future. A society that remains with its wounds permanently open

condemns itself to a continuation of its conflicts and eliminates its

possibilities to live in peace. Justice, truth, forgiveness and

reconciliation are not mutually exclusive or contradictory terms. Our

very remembered

Pope John Paul II said with respect to the following, in his

message for World Day of Peace on 1 January 1997.

I quote: "Forgiveness, far from excluding the search for truth, demands

it. The wrong must be recognized and, where possible, repaired ...

Another essential requisite for forgiveness and reconciliation, is

justice, which finds its justification in the law of God ... In effect -

the Pontiff added - forgiveness does not eliminate or decreases the

demand for reparation, which belongs to justice, but seeks to

reintegrate equally individuals and groups into society. "End of quote.

6 - Faith, hope and charity. The most important I have left for last,

because it's what surrounds and makes everything else possible. Faith in

God because without Him every effort will be useless: "Unless the Lord

builds the house, its builders labor in vain,"

affirms Scripture. Hope in God, because through Him comes us all that is good: "

Blessed are they who have placed their trust in the Lord,"

proclaims St. Matthew in his gospel. Charity, that is love of God and

of our brothers, because we have already seen too much the fruits of

hate in our people. Because charity is what God wanted for us, sent to

us over the sea the image of the Mother of his beloved Son under the

inspiring nickname: the Mother of Charity, Mother Love, Mother of the

country. If what we do for Cuba, we do not do for love, better not do

it.

If all of us who want the good of the nation, of the important internal

dissident movement and the persevering of exile arm ourselves with these

virtues, we will be effective. If we are committed to not let

personalism, or the passions dilute them, we will have won. If we keep

them and transmit them to all our people, we will have secured for Cuba a

happy future.

I end with an expression of loyalty, affection and paternal recognition

to the work of the Catholic Church in Cuba during this difficult stage

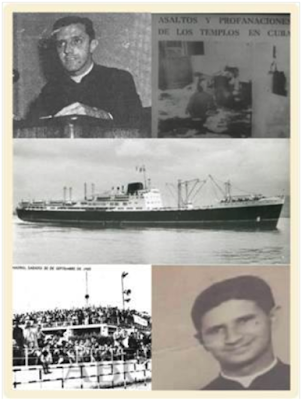

in our history. On February 3, 1959

the first joint pastoral of the Cuban Bishops

saw the light, which focused on the topic of education, those shepherds

launched demands and questions applying to all of the deceptive

revolutionary project that began then. Earlier, only two days after the

triumph of the revolution, the Archbishop of Santiago de Cuba,

Monsignor Enrique Pérez Serantes,

reminded the new government and the entire people why they had fought,

saying: "We want and expect a purely democratic Republic , in which all

citizens can fully enjoy the richness of human rights "End of quote.

Since then, the facts,

well documented also show us the suffering Church,

harassed sometimes

more covertly than others, but always harassed, on the side of the

people of Cuba. This was, perhaps, its most eloquent point with the

pastoral "

Love hopes all things",

of 1993, but there is also a long and rich history, which one day will

be known in all its details, of the generous, brave and quiet labor of

the Church in favor of the legitimate interests and needs of the Cuban

people in these times. It's not for nothing that the loudest cries of

"Freedom!" Heard in Cuba in recent times took place in public places

during the visit of John Paul II in 1998.

I also equally affirm my personal appreciation and respect for the

internal dissident movement in Cuba and I do it from the heart of a

Cuban naturally proud to be exiled, of belonging to this exile committed

to the national destiny, full of men and women of faith and action,

whose merits and virtues are not always fairly valued.

When a happy end could be brought to the prison riots in Atlanta and Oakdale in 1987,

I remember the excitement made me exclaim that day that if I were not

Cuban, I would pay to be. Without a trace of arrogance, with great

respect for all peoples of the world, I repeat it today: I would pay to

be a dissident, I would pay to be an exile, because both are the same:

Cubans, good Cubans trying to be better.

I should apologize for having forgotten the time limit, but I thought

that the important choices we have before us Cubans right now, asked for

these considerations that I wanted to share with you, taking advantage

of the invitation of Father Felix Varela Foundation, which again I want

to thank. Maybe I failed to add one of the virtues we need, is to say

more in less time. But you, who are so generous, will understand,

because you are Cubans like me.

Thank you very much everyone.

Bishop Agustín A. Román

Auxiliary Bishop Emeritus

Miami, December 16, 2006