“All the races of the world are men, and

of all men and of each individual there is but one definition, and this

is that they are rational. All have understanding and will and free

choice, as all are made in the image and likeness of God . . . Thus the

entire human race is one.” - Bishop Bartolomé De Las Casas (1550)

Since it is akin to asking what color Napoleon's white horse is, the definition of human rights ought to be self-evident at first glance. Human rights are those that you have just by virtue of being a person. These rights ought to apply to everyone since they are fundamental to being a human.

The modern concept of a universal human rights standard, despite its simplicity, was not even discussed until the 1550s. In a discussion concerning the rights of the native people of the Americas, Bishop Bartolomé De Las Casas presented a universal concept of human rights for the first time.

“All the races of the world are men, and of all men and of each individual there is but one definition, and this is that they are rational. All have understanding and will and free choice, as all are made in the image and likeness of God . . . Thus the entire human race is one.”

The French revolution is tied the emergence of rights to a particular national experience while appealing to enlightenment values. At the same time critical voices, such as Edmund Burke, emerged that challenged the abstract rights discourse with concrete examples and through his own prior actions provided a working alternative rooted in tradition, and moral values.

|

Bartolomé de Las Casas by Parra |

Why return to these ideas now?

Enlightenment liberalism constructed abstract models that failed to take into account the full complexity of human nature and its contradictions. The French human rights charter declares men absolutely both free and equal. Edmund Burke believed that "full equality" outside of the moral and spiritual sphere is unattainable and a dangerous fiction. First, to permit absolute freedom is to tolerate profound inequalities because people if left to their own devices develop hierarchies. Secondly, to enforce absolute equality requires an all powerful state to repress natural inequalities. The French Revolution: How utopian aspirations led to dystopian results

|

| The execution of Robespierre and his supporters on 28 July 1794. |

The end result is not absolute equality but a small group with great power at its disposal making slaves of the majority. This is what happened in the French Revolution and reached its apex with Maximilien Robespierre, in 1794 with an observation that he applied in governance: "The government in a revolution is the despotism of liberty against tyranny." It is a contradiction in the same way that combining absolute freedom and equality as revolutionary goals are in contradiction and doomed to failure. Robespierre was only applying the logic of enlightenment thinker Jean Jacques Rousseau's who spoke of "forcing men to be free." The "rights" that emerged out of the French Revolution were a rejection of tradition, the Ancien Régime and the Catholic Church more specifically, gave Europe its first modern genocide of peasants in which men, women, and children were systematically exterminated, The Vendee, and the end result was the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and a world war that took three million lives. Edmund Burke, and a conservative conception of Human Rights

|

| Edmund Burke |

In Reflections on the Revolution in France, written less than a year into the French Revolution, Edmund Burke predicted in 1790 that the follies of enlightenment liberalism and its abstractions would lead to widespread slaughter, tyranny, and ultimately a dictatorship.

Burke provides an alternative approach to the defense of human rights that rejects abstractions, defends tradition, but also has a moral sense informed by his Christian faith. Edmund Burke's lifelong opposition to "entrenched and arbitrary power" led him to clash with enlightenment liberalism at pivotal moments. He was the prosecutor who attempted to remove Warren Hastings, the Governor General of India, ten years before the French Revolution, for poor leadership, personal corruption, and mistreatment of the Indians he was responsible for. On February 15, 1788, Edmund Burke opened with a speech which is excerpted below:My Lords, the East India Company have not arbitrary power to give him; the King has no arbitrary power to give him; your Lordships have not; nor the Commons, nor the whole Legislature. We have no arbitrary power to give, because arbitrary power is a thing which neither any man can hold nor any man can give. No man can lawfully govern himself according to his own will; much less can one person be governed by the will of another. We are all born in subjection—all born equally, high and low, governors and governed, in subjection to one great, immutable, pre-existent law, prior to all our devices and prior to all our contrivances, paramount to all our ideas and all our sensations, antecedent to our very existence, by which we are knit and connected in the eternal frame of the universe, out of which we cannot stir.Edmund Burke in the trial against Hastings advocated for the idea that people of different races should not be exploited and of the need for accountability. It was not the first time Burke spoke out against arbitrary rule. In his March 22, 1775 speech on conciliation with America he explained to the British government that the way to keep the allegiance of the colonies was to maintain the identification with civil rights associated with colonial rule warning that if that relation were broken it would lead to dissolution.

Let the colonies always keep the idea of their civil rights associated with your government-they will cling and grapple to you, and no force under heaven will be of power to tear them from their allegiance. But let it be once understood that your government may be one thing and their privileges another, that these two things may exist without any mutual relation - the cement is gone, the cohesion is loosened, and everything hastens to decay and dissolution. As long as you have the wisdom to keep the sovereign authority of this country as the sanctuary of liberty, the sacred temple consecrated to our common faith, wherever the chosen race and sons of England worship freedom, they will turn their faces towards you.Edmund Burke's concept of human dignity as derived from the creator combined with a concept of man's moral equality has deep roots in the Christian tradition which incidentally is where the very language and concept of human rights first emerged in the 1200s in the Catholic Church and was refined by Thomas Aquinas. Edmund Burke's defense of the marginalized, the colonized, and the conquered was rooted not in abstract enlightenment theory but a Christian moral vision of the universe. According to Burke, in his 1796 Letters on a regicide peace, man has freedom but it is not absolute:

As to the right of men to act anywhere according to their pleasure, without any moral tie, no such right exists. Men are never in a state of total independence of each other. It is not the condition of our nature: nor is it conceivable how any man can pursue a considerable course of action without its having some effect upon others; or, of course, without producing some degree of responsibility for his conduct.

Conservative skepticism

The skepticism expressed by conservatives Nigel Biggar and Harrison Pitt in their conversation on human rights is not new. Paleo-conservative writer Thomas Fleming in The Morality of Everyday Life

asks: “If rights are claims to be enforced by government, then what are

‘international human rights’ if not the theoretical justification for

world government?”[Fleming, T. 2007 ] American conservatives are also concerned with the proliferation of rights into areas that undermine traditions.

It has been demonstrated that governments have a history of mass

killing. Why should one think that a world government would be any

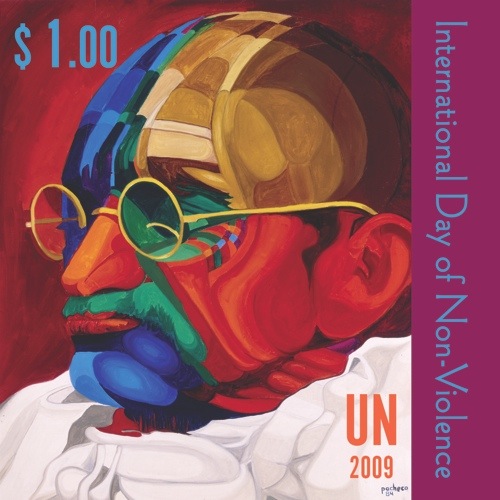

better? The question has not only been raised by American conservatives but also by a man who the official media of the Soviet Union described as a reactionary utopian upon his death in 1948. Mohandas Gandhi

looked upon an increase in the power of the State with the greatest

fear because, although it appeared to be doing good by minimizing

exploitation, it did the greatest harm to mankind by destroying

individuality. Furthermore Gandhi believed that: “Centralization as a system is inconsistent with [a] non-violent structure of society.”

Nature abhors a vacuum.

Despite this skepticism the fact remains

that both human rights discourse and the universality of human rights

emerged out of one of the most conservative institutions: The Catholic

Church. Conservatives must not abandon the conversation on human rights to the Left. Therefore, if one wants to understand how human rights came to be and what can be done to ensure that they can be preserved in a way that, while acknowledging that utopia is unattainable, aims to improve the lives of their fellow humans, one must have a conservative conception of human rights. The Revolution in China, France, Russia, Cuba, and many other countries demonstrate that, when left to their own devices, the Revolutionary's imposition of expanding abstract rights results in a dystopian hellscape rather than a utopian paradise.

No comments:

Post a Comment